Crop Rotation 101

Planting a diversity of rotation crops keeps the soil healthy, breaks disease cycles, and can allow for better water infiltration.

If you were to record any field of potatoes in Washington for five years, you would see that field grow five different crops. Those five crops are part of a scientific and proactive method of rotation farmers use to responsibly manage and improve their lands. Each crop is grown as part of their larger crop production system.

In high rainfall areas of Eastern Washington, such as Spokane and Whitman counties, wheat is the primary crop for farmers. These farmers may also grow canola, garbanzo beans, dried peas, lentils and Kentucky Bluegrass seed in rotation with wheat to improve the crop on each piece of land they own. In drier, non-irrigated areas, farmers will use a fallow rotation to help conserve moisture. In Skagit County, farmers grow more than 80 different crops, and rotational farming allows farmers to break up disease, insect and tillage cycles naturally on land. They often voluntarily “share” land so they can implement healthy rotations on each parcel. Some farmers use cover crops such as clover, rye, vetch and mustard as a rotation and grow them between cash crops when the land would otherwise be bare.

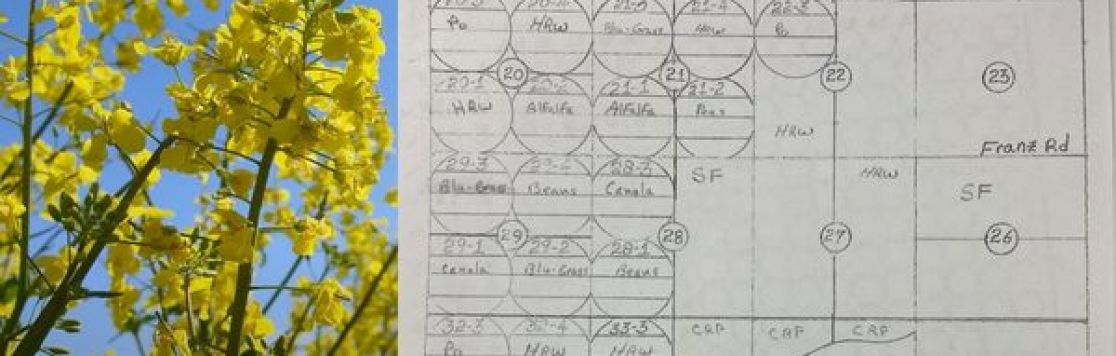

Farmers set goals for what they want their crop rotation to accomplish. Then they develop rotation plans, maps and sequences for each section of their farm to achieve them.

A crop rotation can help to manage soil and fertility, reduce erosion and disease, improve soil health, and increase nutrients available for crops. For example, when a wheat farmer plants a nitrogen-fixing crop, such as peas or lentils, it improves the soil naturally. Another example is potatoes. Potatoes can only be grown one year out of four on the same piece of land because they are highly susceptible to disease. The three years between potato crops allow time for the diseases to die out on that land. One reason Washington potato farmers grow more potatoes per acre than anywhere else is because they have a meticulous rotation. An irrigated potato farmer in the Columbia Basin may use a seven-year rotation like this on a certain field:

Year 1 - Canola

Year 2 - Wheat

Year 3 - Potato

Year 4 - Wheat

Year 5 - Peas

Year 6 - Kentucky Bluegrass

Year 7 - Kentucky Bluegrass

Managing the larger crop production system is such an important part of potato farming that the industry stepped up this year to hire Steve Culman as Distinguished Endowed Chair in Soil Health for Potato Cropping Systems at Washington State University. Culman will address priorities in irrigated agriculture, including the need to better understand and protect the soil.

“Growing potatoes is a highly productive and highly intensive process,” he said. “There’s a wide diversity of rotation crops and grower constraints. Making sense of all those systems will be a grand challenge for me.”

Based at Pullman, his work will take him across the Columbia Basin. “The way things are grown reflect what we value and what we want to pay for, protect and think about. My goal is to improve fertility and the health of our soil, and to do that while we grow food,” Culman said.

Rotations are as important as sunshine, water and nutrients to our farmers. They are one of the most important practices that help set Washington apart and allow us to grow safe and healthy food.